Enemy on the Team - The North Korean IT Worker Trick

Table of Contents

I deal with cyber security every day, both professionally and privately. I audit firewalls, analyse logs, run penetration tests, and speak to IT administrators at companies of all sizes. And one thing keeps coming up: most IT admins don’t even know about the risks they’re underestimating.

They think about ransomware, phishing, and external hackers trying to breach the firewall. That’s understandable - these are the classic threats we grew up with.

But there’s another kind of attack - one that’s much older and far more sophisticated: the enemy within.

There’s a story from summer 2023 that I still find compelling today. It shows how a state-backed hacker group - the North Korean regime - manages not only to infiltrate individual companies, but also to build an entire network of spies. And the best - or worst - part is that the people providing the hardware often have no idea who they’re really working for.

Christina Chapman and the laptop farm in Arizona

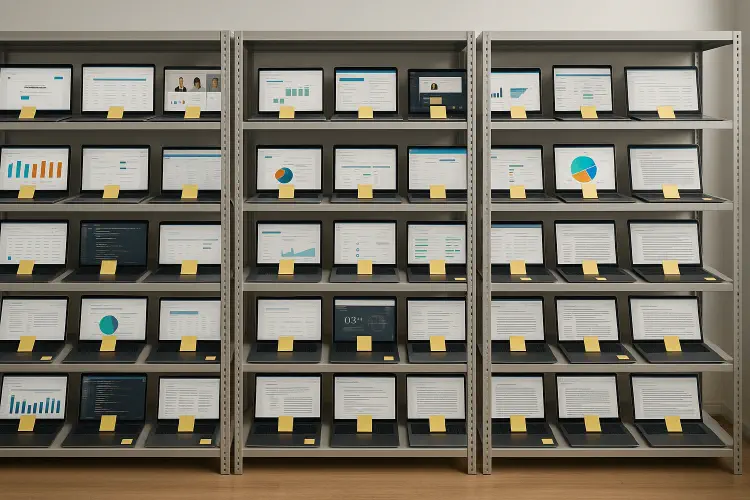

In October 2023, the FBI executed a search warrant at an unremarkable house in Arizona. What they found was unsettling: more than 90 active laptops, each with colourful Post-it Notes attached. Metal shelving, neatly labelled and methodically arranged. A room that turned out to be a so-called laptop farm.

The owner was Christina Chapman. She’s in her mid-50s, works from home, occasionally posts on social media. Nothing suspicious. Nothing to raise eyebrows.

And that’s exactly the perfect cover.

Chapman wasn’t actively recruited as a spy. She was used - by North Korea.

How it all started: a LinkedIn message

In 2020, Christina Chapman received a message on LinkedIn. A stranger calling himself “Alexander the Great” reached out. He made her a low-key offer: she should receive and set up laptops.

Per device: around $300 per month.

It sounded legitimate. It sounded easy. And Chapman was in a tough spot. Her mother had cancer. She needed money for treatment.

She accepted the offer.

What Chapman didn’t know: the person messaging her wasn’t “Alexander the Great”. He was a North Korean hacker. And the laptops shipped to her were corporate devices issued to ostensibly US-based employees; they enabled North Korean developers in Pyongyang to work under false identities.

The insidious mechanism

Here’s how the fraud works:

Fake candidate profiles: North Korean programmers create fictitious LinkedIn profiles. They use stolen photos, forged certificates, AI-generated application videos. They apply via Upwork, Fiverr, and directly to large companies.

The infiltration: They get hired. The company sends them a laptop - a real corporate device with real access to real systems.

The problem: These devices are intended for use in the US only. IP geolocation, device telemetry, conditional access and endpoint monitoring would reveal that the supposed employee in California is actually in China or North Korea.

The workaround: Christina Chapman receives the devices. She notes the password, installs AnyDesk - a remote access tool. The North Korean hacker in Pyongyang takes control of the device, routes their work via Chapman’s Arizona address, and everything looks normal to the company.

Additional camouflage: The network steals the identities of real US citizens, including names, Social Security numbers and addresses. With that data they open new bank accounts. Salary payments are paid there - and are then forwarded to North Korea.

At Chapman’s house, the setup went undetected for three years.

The desperation

Chapman’s chat messages with her handlers show that before long she knew what she was doing: it was criminal. She got nervous. She wrote that it was too dangerous. She wrote that she wanted to stop.

But then her mother died. The medical bills were paid. And Chapman was now in too deep. She was dependent on the money. She was trapped by fear.

She just kept going.

How it was exposed

In 2023, something unexpected happened. A security analyst at Palo Alto Networks noticed something odd: an employee had updated their LinkedIn profile - from a North Korean IP address.

That shouldn’t have been possible.

The internal investigation began. And it quickly became clear: this wasn’t just a few suspicious logins. There were nine employees with direct links to North Korea. And three of them had their laptops shipped to the same address.

A house in Arizona. Christina Chapman’s house.

In October 2023, the FBI moved in. They found the 90 laptops. They were able to show that Chapman had helped infiltrate 309 US companies - including Fortune 500 firms like Nike (which paid nearly $75,000 to a North Korean worker), the communications platform Jeenie, staffing provider DataStaff, a top-five television network, a Silicon Valley technology company, an aerospace manufacturer, a US car manufacturer, a luxury retailer, and a prominent US media and entertainment company. The proceeds: $17.1 million in salaries, directly to North Korea.

On 24 July 2025, Christina Chapman was sentenced to 102 months’ imprisonment (eight years and six months). She confessed. She expressed remorse. But it was too late.

Why this can affect any company

The scenario I’ve described isn’t confined to Arizona. Numerous international companies have already contracted with North Korean IT workers. They don’t notice. They only notice when it’s too late.

There’s another case in this story: a German entrepreneur named Memo, who built a development team in Berlin. He hired three “programmers” - highly qualified, good English, impressive portfolios. A team lead called “Ryosuke Yamamoto” headed the project.

At first, things went well. The developers worked quickly, delivered code, made progress.

But after a few months something changed. Suddenly the programmers kept asking the same questions. They forgot what they’d done before. They seemed far less competent. The three months the project was supposed to take turned into six. Then nine.

That’s a classic sign. The programmers aren’t too dumb. It’s more likely that new people are regularly rotating onto the accounts - under the same false identity. North Korean IT cells are organised along mafia lines. Each unit must fund itself. Programmers are rotated through. The daily routine is strict: 14 to 16 hours a day, under supervision, with a quota.

Memo noticed. He started digging. And then he realised: the people he was meeting on video calls weren’t the people who had actually signed up.

What does this mean geopolitically?

This isn’t a small-time scam. This is state-directed economic espionage that brings North Korea hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

The UN Security Council estimates that between $250 million and $600 million per year flow to North Korea via these IT worker fraud schemes. The money directly funds:

- North Korea’s nuclear programme

- Missile tests

- The development of new strategic weapons

North Korea is under heavy sanctions. The country cannot earn hard currency through normal trade. So it has turned to cybercrime. First it was crypto theft. Then bank heists. Now: thousands of fake IT profiles infiltrated into Western companies.

According to figures published in October 2025, there are an estimated 1,000-2,000 North Korean IT workers active worldwide - operating from China, Russia, Laos, Cambodia and elsewhere.

The United States has offered a reward of $5 million for information on North Korean financial fraud operations.

What does this do to IT security?

This is what worries me most personally. We’re dealing with a threat that comes from the inside.

Remote work, cloud access, and freelance platforms are all legitimate and necessary tools of the modern economy. But they also expand the attack surface.

The classic security architecture works like this:

- Strong firewall on the outside

- Trusted zone inside

- Whoever is inside is trusted

But what if the person on the inside isn’t actually the person you hired?

Christina Chapman wasn’t the threat. Chapman was the infrastructure. She was the gateway. The real threat was sitting in Pyongyang, on another continent, under a false name.

How to protect yourself (in practical terms)

Multiple agencies have issued concrete recommendations. I’ll add my own experience:

1. Verify applicant identities - really verify them

Video calls matter, but:

- Watch for long pauses before answering.

- Look for the candidate reading from notes.

- Check the background environment (does it look real or green-screened?).

- Modern AI tools can fake video interviews - that’s well documented. Use liveness checks.

Contact previous employers directly. Don’t use the email on the résumé - look up the company’s real phone number and call.

Use background checks. LinkedIn verification. National and international credit reference agencies and right-to-work checks where applicable.

2. Secure remote workstations with geofencing and MFA

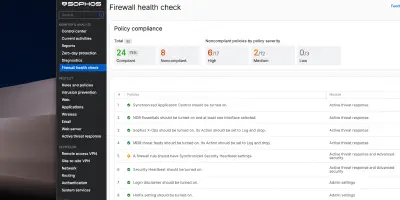

Geofencing and conditional access: enforce country/region and ASN policies at your identity provider and via MDM. Trigger alerts on logins from high-risk geographies and “impossible travel” events.

Multi-factor authentication on all critical systems. Not just a password. SMS is not secure. Prefer hardware security keys or TOTP apps.

Set session duration and anomaly thresholds: if someone consistently works 14-16 hours straight (which can indicate shift rotations), that should be flagged.

3. Network monitoring for suspicious connections

Log source IPs at the identity and VPN layers. If different employee accounts are accessed from the same residential IP, that’s suspicious.

Monitor for unsanctioned remote access tools (AnyDesk, TeamViewer, etc.). Block or quarantine where found.

Monitor DNS and egress traffic. Alert on connections to domains/IPs associated with DPRK threat actors and command-and-control infrastructure per threat intelligence feeds.

Time zone analysis: if a supposed US-based employee consistently works during Korea Standard Time business hours (UTC+9), it’s suspicious.

4. Issue hardware only centrally and with full traceability

Never: an employee orders their own laptop and the company pays for it.

Always: use central IT management. Devices are issued by your IT team. MDM (Mobile Device Management) is enabled.

Tracking: every device has a unique serial identifier. Maintain an asset register and chain of custody for every assignment.

5. Know the red flags - and take them seriously

- A new employee repeatedly asks about topics already covered.

- A remote employee consistently works at unusual times.

- A junior developer suddenly delivers code that doesn’t match their previous quality.

- Different-looking webcam videos in meetings (it could be different people using the same identity).

- An employee’s onboarding is delayed because the candidate is “unavailable”.

Conclusion: trust is not a security model

The Chapman case highlights something fundamental: the danger often comes from inside because it masquerades as an external one.

We cling to the illusion that if someone has signed a contract, has strong LinkedIn endorsements, and comes across well on a video call - then they’re trustworthy.

That’s no longer true.

The North Korean IT worker scam isn’t an anomaly. It’s a business model. A business model run by a state-backed hacker group that understands:

- Remote work has become normal.

- Freelance platforms are established.

- Video interviews can be faked.

- Most IT admins think about external threats, not internal ones.

And that’s why it works.

For companies that are scaling fast or trying to save costs, this fraud is particularly dangerous. Recruiting takes time. Background checks cost money. Video interviews are easy. And a well-trained programmer offering their services at 20% below market rate? That’s tempting.

But every IT admin, every security owner, every hiring manager needs to ask themselves:

How do I really know I’m talking to a real person?

If you answer honestly, the answer is often: I don’t.

And that’s what makes Christina Chapman’s story so important. She isn’t just a single woman in Arizona who received and set up laptops. She’s a symbol of a much bigger reality: the digital world is not as transparent as it appears.

Behind good English, a convincing LinkedIn profile and smart answers in a video interview could be a government operative from a foreign regime.

The only sensible approach is zero trust: do not assume trust. Verify explicitly. Monitor continuously. And have the systems in place to notice when something’s off.

That’s the new reality of cyber security. The danger doesn’t come from outside. It comes from inside, because it impersonates an employee.

Best regards

Joe